As the world moves away from a full and no-strings-attached globalization, focused on growth and efficiency, and heads toward more fragmented geopolitical alignments, competing technology standards, higher costs, and greater constraints, technology companies and their leaders must navigate a difficult path.

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and the interaction of these with other unforeseen events have caused and have been causing some problems for global supply chains for a couple of years now.

And yet some supply chains have since reorganized, thanks in part to the easing of restrictions on a global scale: although continued Chinese lockdowns contribute to risk factors, it is recent news that China has reduced the amount of time travelers entering the country must spend in quarantine and removed a major restriction on international flights1, in a sign of limited easing of its strict zero Covid policy.

Markets reacted positively to the changes: Hong Kong's Hang Seng Index rose 7% just after the midday break on the day of the announcement, and on the same day mainland China's Shanghai Composite Index rose 2.5%.

Yet risk factors persist for the global economy: among them, the prolonged trade war between the U.S. and China.

One of the keywords that recurs most in the debate between China and the United States, and which represents the greatest cost of this period of tension, is decoupling2, or the prospect of disentanglement between the world's top two economies, which will lead to the relocation of U.S. firms' production out of China in sectors deemed strategic.

In this context lies the crucial competition for technological superiority, most evident in the semiconductor industry.

Semiconductors: crisis of the key drivers of the global economy

Semiconductors are one of the key drivers of the global economy: in fact, they are an essential component of electronic devices and enable advances in communications, computing, healthcare, military systems, transportation, clean energy and countless other applications.

The semiconductor crisis that began in 2020 affects dozens of areas of industrial production and has led to severe shortages and expectations among consumers for graphics cards, video game consoles, automobiles, and other electronic devices3.

The cause of the global crisis is a combination of several events, including the trade war between China and the United States and a drought at historic levels in Taiwan. Indeed, chip production requires huge amounts of water: facilities at TSMC, the world's largest independent semiconductor factory, use more than 63.000 tons of water per day4.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic was the main cause of the crisis. As a result of the global shutdowns, manufacturing plants were closed, causing chip inventories to be depleted and many strategically important industries around the world to grind to a halt.

The difficulty of finding computer chips amid global semiconductor shortages is being felt by data logger manufacturers, central elements of digital supply chains: computer chips are the key parts for GPS trackers and sensors, demand is high, but there is an alarming shortage problem.

Automakers, for example, had to halt production or ship unfinished products, and the dwindling supply of vehicles coupled with growing consumer demand generated an additional inflationary boost – on top of that caused by sanctions on Russia's energy industry – affecting millions of consumers.

“Semiconductors are an essential component of electronic devices and enable advances in communications, computing, health care, military systems, transportation, clean energy, and countless other applications.”

Against this highly volatile backdrop, Countries and regional blocs have begun to explore ways to secure a certain supply of advanced chips, subsidizing domestic industries with public money, weakening international trade networks, further exacerbating tensions at work in the global economy, and moving toward a direction of deglobalization – of which decoupling is one of the most tangible manifestations.

So let's look at how tensions between the U.S. and China are changing the global semiconductor supply chain landscape.

US and China: chess match between superpowers

The U.S., in a pattern of continuity between the previous Republican administration and the current Democratic administration, continues to restrict trade with China and increase regulatory control over Chinese companies operating in the United States.

The CHIPS and Science Act, which establishes investments and incentives to catalyze investment in domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the United States, and to support independent research and development and the supply chain, was signed into law by President Joe Biden on August 9. It is a monumental legislative initiative, worth $280 billion over the next ten years: of this, about $52.7 billion is earmarked for semiconductor manufacturing, R&D and workforce development, with another $24 billion in tax credits for chip manufacturing. Also, $3 billion is planned for programs targeting innovative technologies and digital supply chains.

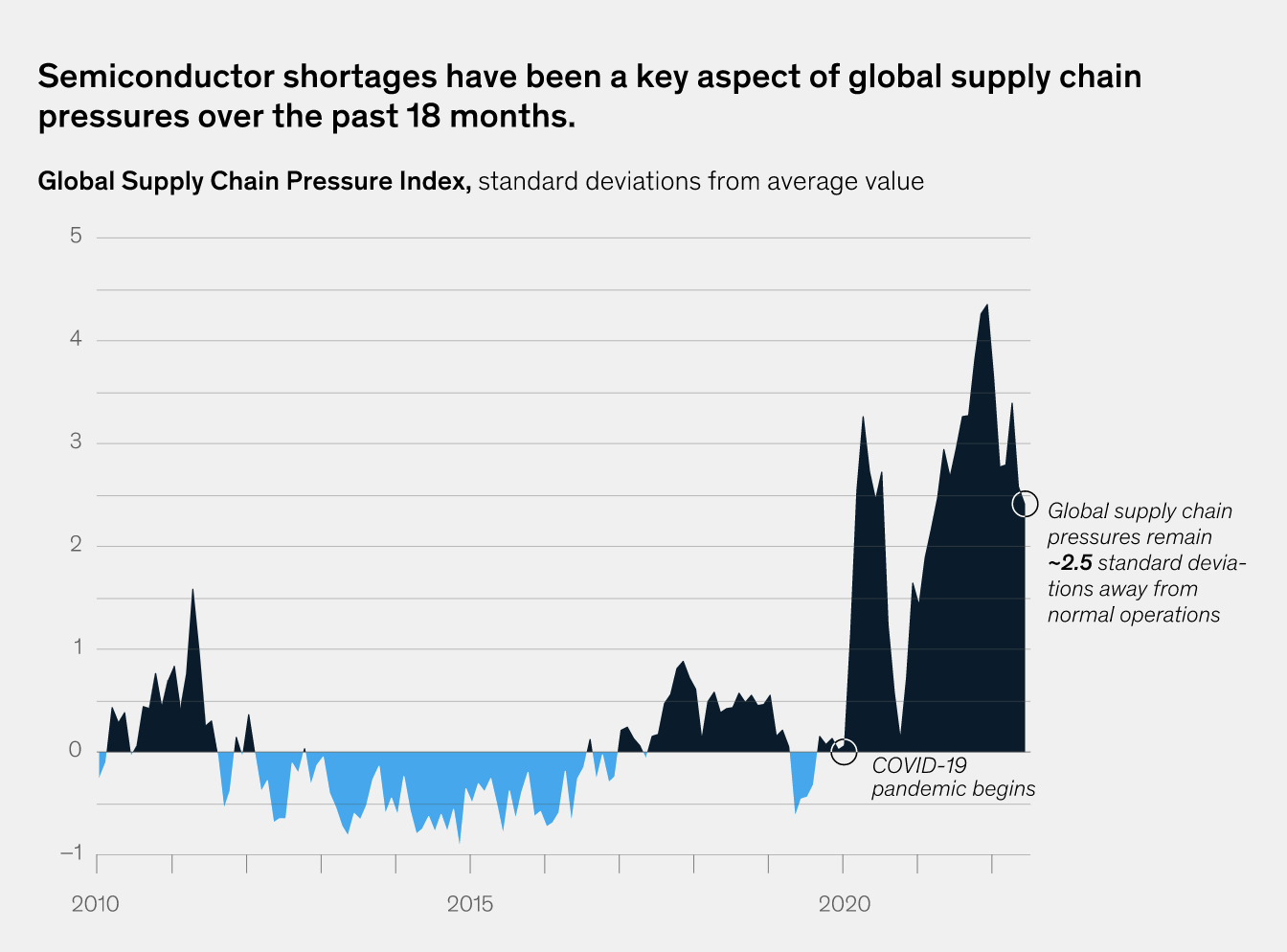

One of the raison d'être of the CHIPS Act is that according to U.S. government statistics, the United States produces 12% of the world's semiconductors, up from 37% in the 1990s5. Many U.S. companies depend on foreign-made chips, and the fragility of these supply chains has been exposed in the past 18 months. In addition, McKinsey research6 estimates that global demand will continue to grow, with semiconductors set to become a $1 trillion industry by the end of the decade.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, S&P Global PMI Commodity Price and Supply Indicators

But in addition, on October 7, the current U.S. administration introduced a set of export controls that prohibit Chinese companies from purchasing advanced chips and chip-making equipment without a license. The rule also limits the ability of "U.S. persons" – including U.S. citizens or green card holders – to provide support for the "development or production" of chips at certain manufacturing facilities in China7.

There have however been some hints of collaboration between the United States and China. Last May, Shanghai-based Semcorp Advanced Materials Group announced that it would open a manufacturing plant in Sidney, Ohio, to make separator films (a key component of electric vehicle batteries).

In August, the two governments also reportedly reached an agreement that would allow U.S. officials to inspect audits of listed Chinese companies. The agreement could prevent the delisting of more than 200 companies valued at about $1 trillion and avert an explosive financial crisis8.

Conclusions

We have seen how the risks of decoupling between the U.S. and Chinese economies can be a serious risk factor for the world economy – simply consider that even Lam Research alone, which provides semiconductor equipment and services, reported in late October that it could lose between $2 billion and $2.5 billion in annual revenues in 2023 due to U.S. export restrictions9.

It seems more necessary than ever to try to work for stability in diplomatic relations so as to keep competition on economic tracks, without trickle-down effects in the realms of sanctions and war.

The U.S. and China would mutually benefit from working together to make semiconductor supply chains safer and more stable by increasingly investing in sustainable technologies.

Notes

- See the CNN article titled China scraps Covid flight bans, cuts quarantine for inbound travelers

- See the ISPI article titled Cina-USA: il decoupling è davvero possibile?

- See the Bloomberg article titled How a Chip Shortage Snarled Everything From Phones to Cars

- See the New York Times article titled Taiwan is facing a drought, and it has prioritized its computer chip business over farmers

- See Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors and Science Act of 2022, Section-by-section summary, US Department of Commerce

- See the McKinsey report titled The semiconductor decade: A trillion-dollar industry

- See the CNN article titled US curbs on microchips could throttle China’s ambitions and escalate the tech war

- See the report by Bain & Company titled US-China Decoupling Accelerates, and Shockwaves Spread

- See note 7